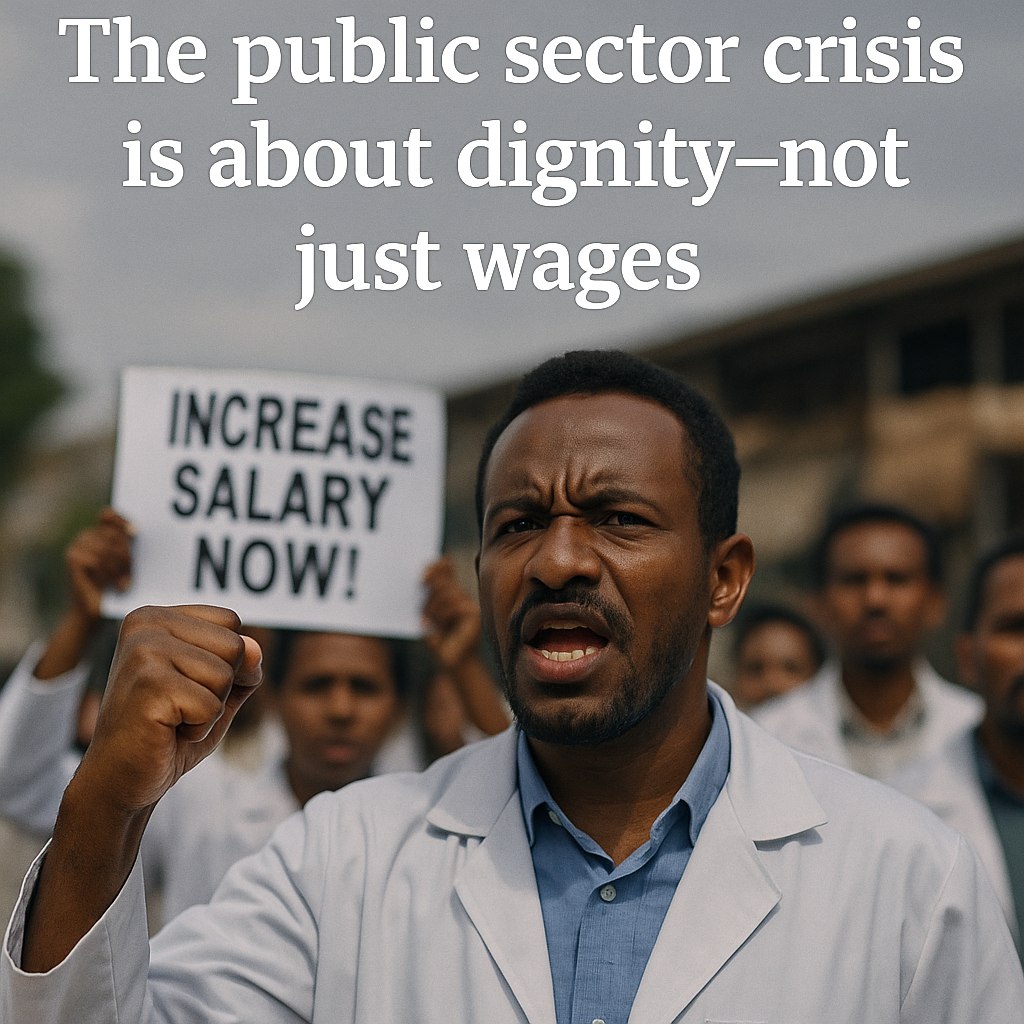

The public sector crisis is about dignity—not just wages

Contributed by Ameha Hailemairam

Soaring living costs, stagnant wages, and anti-worker policies have pushed Ethiopia’s health workers to the brink—but they are fighting back like never before.

In recent weeks, health professionals across Ethiopia have staged protests, demanding salary increases and the recognition of long-denied benefits. These are the people who staff hospitals, clinics, and health posts—the backbone of the nation’s health system. Their frustration has reached a breaking point, with unions warning of nationwide strikes if the government continues to ignore their pleas.

The discontent among health workers reflects a deeper crisis: an erosion of both fair pay and basic respect for those who serve on the front lines of healthcare. Once, a career in medicine in Ethiopia promised a stable and dignified life. That is no longer the case.

Low wages and inadequate benefits are driving a wave of health worker migration. Many, disillusioned by the realities at home, are seeking opportunities abroad, often embarking on perilous journeys. This exodus is not just a personal tragedy for those who leave; it’s a symptom of a broader collapse in the country’s healthcare system.

Ethiopian health workers today earn wages that barely cover the cost of food and housing, let alone education, transportation, or savings. Many are forced to make impossible choices—neglecting their own well-being and their families’ needs while working long hours to care for others. The disparity is stark: senior specialist doctors earn less than USD 100 a month before taxes—barely enough to survive.

A national survey In 2022 found that nearly a third of physicians planned to leave the medical profession within a year, while nearly half reported deep dissatisfaction with their jobs.

The consequences of this discontent are already visible.

Ethiopia ranks among the top five countries in Africa for the emigration of medical professionals, yet it has only 0.1 physicians per 1,000 people, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO’s recommended minimum is 4.45 per 1,000—underscoring the severity of the crisis.

Public sector workers, in particular, are bearing the brunt of the economic pain. Inflation has devoured their purchasing power, pushing many below the poverty line. According to the International Monetary Fund, some of Ethiopia’s lowest-paid public service workers now earn so little they cannot meet even basic living standards. Yet these are the very people the government relies on to implement its ambitious reforms.

While the federal government’s fiscal deficit is projected to narrow to 1.7 percent of GDP this year, without a corresponding increase in public sector wages, its reform agenda is at risk of failure. The logic is clear: underpaid, overworked, and demoralized workers cannot drive the changes Ethiopia desperately needs.

The civil service is at a breaking point. A recent World Bank report paints a stark picture: a system that has expanded rapidly—by an average of seven percent per year over the past five years—yet is now buckling under the weight of inadequate pay, crumbling infrastructure, and widespread disillusionment. The average public sector salary ranges from USD 29 to USD 56 a month, and when adjusted for inflation, real wages have steadily eroded.

Low wages and poor working conditions are not just a burden on Ethiopia’s public employees—they are directly undermining the effectiveness of the nation’s institutions. Nowhere is this more apparent than in healthcare, where inadequate pay has driven many professionals to seek work abroad or in the private sector, leaving public hospitals and clinics chronically understaffed.

The story is similar in education, where teachers, unable to make ends meet, are abandoning classrooms for better-paying opportunities elsewhere, even as the country struggles to meet its growing educational needs.

This is not merely an economic issue. It is a matter of rights.

Under Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), to which Ethiopia is a party, every citizen has the right to an adequate standard of living—including sufficient food, clothing, and housing. Yet, Ethiopia’s current economic realities stand in stark violation of these principles.

With inflation soaring to around 35 percent, while annual wage increases stagnate at a mere four percent, public sector workers—who form the backbone of the nation’s development—are unabto to afford the basic necessities of life. The government’s failure to address this growing disparity not only erodes the dignity of its citizens but also flouts its legal and moral obligations to uphold fair living standards under international law.

Urgent reforms are needed. The government must prioritize policies that make housing affordable, incentivize private sector investment in affordable housing, and ensure fair wage practices that reflect the true cost of living. Without such action, the cycle of poverty and disillusionment will only deepen.

Instead, recent policy choices have played a part in exacerbating the crisis. The government’s decision to raise public service fees by as much as 700 percent—including for essentials like electricity, telecommunications, water, and crucial identification documents—has placed an even heavier burden on households. These costs compound existing financial pressures, pushing many deeper into economic hardship and making it even more difficult to afford housing and other basic needs.

A different approach is urgently required. The government should invest in affordable housing initiatives, including tax credits and subsidies for developers who build low-cost homes. Public-private partnerships could play a critical role, offering incentives such as reduced taxes or low-interest loans for affordable housing projects. Collaborative efforts with African banks, nonprofits, and international partners could help finance large-scale housing solutions that meet the needs of civil servants.

Cooperative housing models, where public employees pool resources to build homes collectively, offer another viable solution—one that promotes community ownership, reduces costs, and ensures long-term affordability.

Ethiopia must also look inward for solutions. By embracing local materials and labor—such as rammed earth, bamboo, and other indigenous, cost-effective building techniques—the country can reduce construction costs while promoting sustainable, eco-friendly housing options.

Ultimately, the core issue is dignity. Stagnant wages and rising costs have stripped Ethiopia’s civil servants of a basic standard of living. Public sector workers receive salary increments only once every three years—far too infrequent to keep up with the pace of inflation. Even with these periodic adjustments, many still struggle to pay for food, electricity, transportation, and utilities.

The solution is clear: Ethiopia must establish a system of regular wage reviews, tied to inflation, to ensure fair compensation. In the short term, targeted measures such as housing and utility allowances, food subsidies, and social welfare programs can offer immediate relief.

A comprehensive approach—combining wage reforms, housing initiatives, and stronger worker protections—is essential to restoring dignity, safeguarding human rights, and ensuring equitable growth. The government’s failure to act risks not only deepening the crisis but also undermining the very foundation of its public sector—and, by extension, its future.

It’s time for Ethiopia to invest in its workers—because without them, there can be no progress.

(Ameha Hailemairam holds a Master of Arts in Economics from Indira Ghandi National Open University, with experience in the banking sector and as a financial analyst.)